Despite all the physics involved, the life and death of clouds seems almost organic, even human. Like us, they’re continually becoming and dying, forming and dissipating. Yet the absence of cloud is always temporary. “They have a contradictory quality of being both ephemeral and enduring,” says Pretor-Pinney.

Cloud cover has varied throughout the planet’s deep history—sometimes dramatically. But computer models mimicking the future role of climate change struggle with clouds’ micron-level physics. At the level of individual droplets, “there are not enough computers in the world to run the data and model it,” says Goldblatt.

Some change is certain in a warming world, if only because the atmosphere holds about seven per cent more water vapour for every degree rise in temperature. Meanwhile, humans keep adding to (and sometimes subtracting from) cloud-forming nuclei with aerosols, or more air travel, or cleaner ship exhaust.

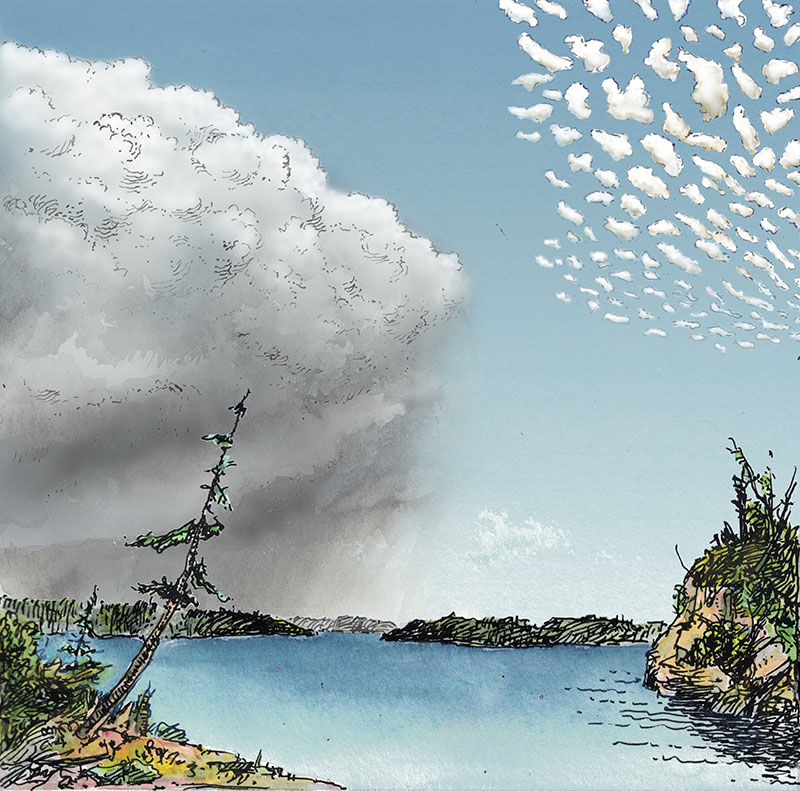

“In cottage country, because of a warming climate, we might expect more risk of convective storms, hotter weather, and more evaporation,” says Goldblatt. The planetary impact, however, depends on the mix of cloud cover. High ice-crystal clouds boost planetary warming. Low, dense clouds have a net-cooling effect. There’s recent evidence that fewer low clouds over the ocean have contributed to recent warming. But the ultimate result, says Goldblatt, remains “a very big and very difficult question in climate science.”

In an old Peanuts comic, Lucy, Linus, and Charlie Brown lie on a grassy hill. “If you use your imagination, you can see lots of things in the cloud formations,” says Lucy, asking Linus and Charlie Brown what they see. Linus spies Biblical scenes, the outline of British Honduras, and “the profile of Thomas Eakins, the famous painter and sculptor.” When Charlie Brown’s turn comes, “I was going to say I saw a ducky and a horsie,” he says. “But I changed my mind!”

For most of history, clouds were named Charlie Brown-style, for what they did (rain cloud), or what they looked like (horsie). When British pharmacist Luke Howard pioneered modern cloud classification in 1802, he added the scientific gloss of Latin, but appearance still mattered. Howard’s cumulus cloud, for example, is Latin for “heap.” Then there’s stratus (“layer”), nimbus (“rain”), and cirrus (“lock of hair”).

Later additions included altitude (“alto” for mid-level) and more descriptive adjectives. The result is two- or three-part names, some invested with a poetic or even comic sensibility. Consider the cumulus humilis (hardly anyone else does)—a low-level, humble heap of fluff. Or the stratocumulus castellanus, a castle in the sky with diaphanous battlements. Pretor-Pinney is particularly chuffed by asperitas (“roughness”), an ominous cloud with a wavy underbelly first suggested by the CAS and formally adopted by the World Meteorological Organisation’s International Cloud Atlas in 2017.

Names give humans a grip on these amorphous objects, with practical payoffs. It’s good to know that a billowing cumulonimbus may bring thunder and lightning. Or a cirrocumulus “mackerel sky” promises unsettled weather. (“Mackerel sky, mackerel sky. Not long wet. Not long dry.”) “I’m not an expert on all the cloud names,” says cottager Gord Baker. “But I know enough to take proactive action.”

There’s also growing evidence that the mindful appreciation of the sky is good for you. Studies suggest the kind of awe that comes from watching the slow unfurling of a cumulus or the windswept hooks of cirrus uncinis (a.k.a. mares’ tails) could reduce inflammation, anxiety, and stress while boosting immune function and sense of wellbeing. The mere act of elevating your gaze, writes University of Waterloo psychology professor Colin Ellard, seems to help your brain switch gears from mundane tasks to Big Thoughts. As he writes in his book, Places of the Heart, looking skyward towards clouds, mountain peaks, or even the vaulted ceiling of an ancient cathedral helps “dissolve the earthly chains that bind us to the prosaic events of ordinary life.”

Of course, cottagers already know this. Call it feelings of transcendence, flow, mindfulness, or just relaxation, they’re all a regular byproduct of gazing skyward from docks, hammocks, and canoes. The key, says Pretor-Pinney, is to take the time to do it—to observe the heavens and seize the opportunity that clouds present. It means “being prepared to stop what you are doing, wherever you are, to spend a few moments” gazing upward, a practice that’s “good for the mind, good for creativity, and good for the soul.”

For Barbara Havrot, clouds are daily performance art. She records time-lapse videos from her cottage window—the morning mist swirling off the river, the clouds building overhead and sweeping towards the east, and the sunset eventually burnishing their bellies. This summer, she hopes to share the fascination with her grandson. “I’m really looking forward to looking at clouds with him.”

And when Barbara and her grandson look high overhead, they’ll see a mix of air, dust, and water create something beautiful and fleeting—a moment to be briefly held and appreciated, before being released into the busy torrent of life.

Keep looking up, says Pretor-Pinney. “To spend some time with your head in the clouds,” he adds, “helps you keep your feet on the ground.”

Writer Ray Ford favours cirrus clouds lacing the blue skies near his Powassan, Ont., home.

This story originally appeared in our August ’25 issue.

Cloud atlas

Altocumulus (left); cumulus (middle); and cumulonimbus (right). Illustration by Jim Stewart

Altocumulus (left); cumulus (middle); and cumulonimbus (right). Illustration by Jim Stewart

Cumulus

The first cloud you drew as a kid, this puffy, floating cauliflower is a low-level (up to 2,000 metres in altitude), convective classic.

WEATHER FORECAST

Usually a short-lived fair-weather cloud—unless it bulks up. (See cumulonimbus.)

COTTAGE FORECAST

Get outside!

PRETOR-PINNEY SAYS

“It looks so damn comfortable. Who hasn’t dreamt of falling asleep in the cumulus’s plump, white folds?”

Cumulonimbus

The T-Rex of the skies rises up to 15 kilometres, often with a posse of “accessory clouds,” including the wall cloud, the shelf cloud, the lid-like pileus (from the Latin for “felt cap”) incus (“anvil”), and the udder-like mammatus.

WEATHER FORECAST

A bringer of rain, thunder, lightning, and sometimes hail. Also known to toss in the odd tornado or microburst.

COTTAGE FORECAST

Best admired from a distance, and when the lightning begins, indoors.

PRETOR-PINNEY SAYS

“A cumulus with ambitions to take over the world.”

Cirrus (left); cirrostratus (right). Illustration by Jim Stewart

Cirrus (left); cirrostratus (right). Illustration by Jim Stewart

Cirrus

High (5,000 metres or more) ice- crystal wisps, surfing winds of more than 160 km/h.

WEATHER FORECAST

May be the fine-weather precursor to an approaching weather system.

COTTAGE FORECAST

“See in the sky the painter’s brush, the wind around you soon will rush.” In other words, carpe diem while the cirrus is visible.

PRETOR-PINNEY SAYS

That cirrus are “harbingers of a ‘deterioration’ in the weather only adds to their fragile beauty—aren’t the most delicious things the ones we know can’t last?”

Cirrostratus

A thin whitewash of ice crystals above 5,000 metres.

WEATHER FORECAST

Is the layer a uniform veil? Expect an incoming warm front that brings persistent rain within a day. Are the strands wispy? Could just be light drizzle.

COTTAGE FORECAST

Look for spectacular optical effects as light strikes the crystals, including sun dogs and haloes around the sun and moon.

PRETOR-PINNEY SAYS

“High milky veils, which most people barely notice.”

Nimbostratus (left); altocumulus (right). Illustration by Jim Stewart

Nimbostratus (left); altocumulus (right). Illustration by Jim Stewart

Altocumulus

Mid-level (2,000 to 5,000 metres high) lumpy clouds, often forming a layer of similar-sized cloudlets.

WEATHER FORECAST

Settled conditions, at least in the short term.

COTTAGE FORECAST

Book a seat and order drinks for the sunset (or sunrise) show, as a succession of reds, oranges, pinks, and yellows illuminate the rumpled cloudlets.

PRETOR-PINNEY SAYS

Altocumulus are like “layers of bread rolls in the sky.”

Nimbostratus

A thick, largely featureless but sometimes ragged grey blanket reaching up to about 5,000 metres. The U.K.’s Met Office calls it “probably the least picturesque of all the main cloud types.”

WEATHER FORECAST

Rain or snow. Lots of rain or snow.

COTTAGE FORECAST

Two words—Monopoly tournament.

PRETOR-PINNEY SAYS

“Not exactly a dull cloud… but it wouldn’t get far in a cloud beauty contest.”