Tom Thomson was born in Claremont, Ont., on August 5, 1877, and moved to the family farm at Leith two months later. Art historian Joan Murray has called him “the most influential and enduringly popular Canadian artist of the early 20th century.” Trained as a graphic artist, he turned a hobby of painting landscapes into his life’s calling, leaving behind some 50 full canvases and more than 400 sketches in a short career that ended tragically at age 39.

July 8, 2024 will be 107 years since the painter vanished under unusual circumstances, his body surfacing in Algonquin Provincial Park’s Canoe Lake seven days later with a bruise on his left temple and fishing line wrapped around one ankle. At the time, his death was determined to be an “accidental drowning” by the park superintendent, who wanted to keep any news coming out of his jurisdiction low key. Algonquin Provincial Park was then less than a quarter-century old, and its creation in 1893 had been controversial regarding who would be allowed to do what in the vast territory.

The accidental drowning conclusion was then confirmed by a North Bay, Ont., coroner who travelled to Canoe Lake by train, stayed overnight, held a brief hearing, yet never examined the body. Thomson had already been buried by kind souls who could not bear seeing the body deteriorate as it lay trussed to an island root in the warm summer lake water.

It is fair to ask, would Tom Thomson be as famous had he lived on to old age and left hundreds more paintings? Impossible to know, but the mystery assuredly feeds into the fame. Thomson’s death has been subject to wise and wild theory. One of the wildest, recorded by local historian S. Bernard Shaw, proposes—perhaps a bit tongue-in-cheek—that the tragedy was caused by a rare, spontaneous waterspout that plucked the painter from the bay where he’d been fishing, took him high into the sky while the fishing line spun about his ankle before the paddle struck his head and the spout dissipated. Seven days later, it was thought that a little girl fishing with her father snagged something, and the painter’s body slowly surfaced. No paddle was ever found, leaving many to speculate as to how canoe and body ended up so far from shore.

“Tom Thomson continues to seduce and beguile. He lies in the grey mists between fact and fiction, like an elusive shadow only glimpsed from the corner of your eye”

There were rumours of bad blood between Thomson and an American cottager of German heritage (this being wartime). They had a run-in on the water, Thomson fishing from his canoe and the cottager brushing close in a boat. There had also been a drunken party the night before at one of the fishing guide camps. Moonshine was easily obtained in the park in those days, and Thomson was known to enjoy a drink or several.

Courtesy Library and Archives Canada

Courtesy Library and Archives Canada

Daphne Crombie, who had stayed with her husband at the same lodge on Canoe Lake where Thomson had a room, gave an interview in the 1970s in which she claimed that Annie Fraser, wife of Shannon Fraser— proprietor of Mowat Lodge, where Thomson often stayed—told her that Tom and Shannon had fought over money. Tom had lent Shannon money for a canoe purchase. According to Annie’s story, Shannon had struck Tom and Tom fell into the fire grate, hitting his temple. Convinced that Tom was dead, Shannon and Annie had tied his foot to a weight, placed the injured-or-dead painter in his canoe, and used another canoe to haul Thomson’s out into deep water and then dumped the contents. Daphne further claimed that Annie had found letters from Winnie demanding that Tom get the money so he could buy a new suit. There was a baby coming, the letters supposedly implied, and they would have to be married. Winnie’s reputation when I knew her was forceful and outspoken, so it’s possible she would be so direct.

Not surprisingly, this began new speculation as to whether there was indeed a child involved. The social records of the weekly Huntsville Forester show that Winnie and her mother left town that fall for the Philadelphia area—no known relatives there—and did not return until Easter 1918, some nine months after Thomson’s body had been found. Further investigation, however, was never able to establish if a baby was, in fact, born and given up to adoption.

It was Winnie who, with the blessing of the Thomson family, undertook to have the body exhumed at Canoe Lake and taken to the family plot at Leith. A previous undertaker had embalmed the body, and it had been placed in an inexpensive casket before burial in the little Canoe Lake cemetery. Winnie engaged an undertaker from Huntsville to complete the job. This second undertaker arrived under dark, insisted on working alone through the night, and, come morning, had a sealed casket, as required by rail regulations, to return to Leith for burial in the Thomson family plot. It is not believed anyone ever looked in the casket, despite two elderly ladies later claiming the family had checked. The Canoe Lake locals were dubious that the casket they helped load on to the train held anything but a few shovelfuls of dirt and stone.

Nearly four decades later, in fall 1956, a few Canoe Lake locals and cottagers, including family court judge William T. Little, decided to see if Tom’s body had ever actually been exhumed from the cemetery on a hill overlooking the lake. There were still old-timers around who thought they knew how close to that huge birch tree the initial burial had taken place. After several holes failed to produce anything, they did finally find a rotting casket and human remains, including the bones of a human foot. They took their discovery across the lake to the Taylor Statten Camps, where Dr. Harry Ebbs examined the bones. Ebbs’ account has him return to the gravesite with the diggers to collect more bones, from a lower leg, which he then packed up and took with him back to Toronto. Once there, Ebbs said he visited the attorney general’s office, where he was asked to return to the site with government representatives. Ebbs obliged, and the second group obtained additional remains, including a skull with a contusion on the left temple. Ebbs believed they had found the remains of a Caucasian man, approximately Thomson’s height. A forensic examination would take place under the auspices of the attorney general’s office. The diggers were certain they had found Tom exactly where local rumour had claimed he had never left.

Future Group of Seven member Arthur Lismer, left, fishes with Thomson circa 1914.

Future Group of Seven member Arthur Lismer, left, fishes with Thomson circa 1914.

Photo courtesy John Little

A few weeks later, however, the October 19, 1956, edition of the Toronto Daily Star headlined “ALGONQUIN PARK BONES NOT THOSE OF THOMSON.” Ontario Attorney General Kelso Roberts reported that officials had determined the remains were not of Thomson, but rather of a much younger, “male Indian or half-breed.” Other sources found the patient may have died after a complicated trephination operation following a brain hemorrhage. Outraged by such a preposterous proposal, Dr. Ebbs stormed back to Queen’s Park and met with the minister but received no satisfaction. The case was closed as far as the provincial government was concerned. Dr. Ebbs was told the province “did not wish to have the thing opened up and any more fuss.”

Dr. Ebbs, however, had photographs of the skull that the men had unearthed at Canoe Lake. It had been taken on the then-new Kodak Stereo, a 35 mm camera that used two lenses to take twin shots that could then be seen with depth perception in a dedicated viewer.

When I was preparing my 2010 book, Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him, the Statten family, which Dr. Ebbs had married into, provided me with one of those photos. I was then able to connect with Dr. Ronald F. Williamson, who worked in the department of anthropology at the University of Toronto. He is also founder of Archaeological Services, which specializes in identifying remains. Dr. Williamson and his team went to work using the most modern equipment to measure and compare the photograph of the skull to known photographs of Tom Thomson. The team reported back that “…there is no morphological characteristic that suggests the skull belongs to anyone but Tom Thomson.” The plot thickens!

So there you have the mystery—sorry, mysteries. How did Tom Thomson die? Was it an accident, suicide, or murder? Who was exhumed at Canoe Lake in 1956? An Indigenous man, smaller and younger than Thomson? Or was it Thomson himself, his body never having been exhumed in 1917 and taken to Leith for burial, where to this day visitors leave flowers and coins on his stone.

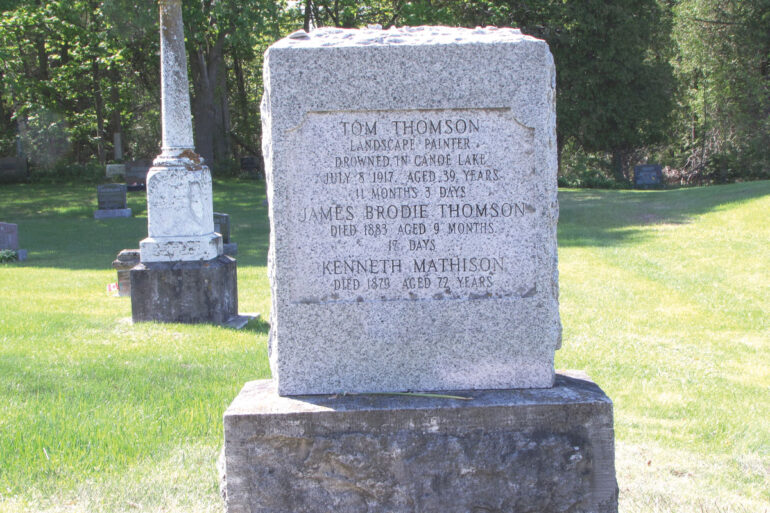

The Thomson family headstone in Leith. Photo by commons.wikimedia.org/tabercil

The Thomson family headstone in Leith. Photo by commons.wikimedia.org/tabercil

For what it’s worth, I believe Thomson was never exhumed and taken to Leith for a family funeral. I interviewed Daphne Crombie at length and found her to be convincing, though she had obviously taken Annie Fraser at her word. Annie told a similar tale to a family in Huntsville that later contacted me. I also believe that the whole story will never be known, which is a large part of what makes it so endlessly fascinating.

In recent years, multiple mysteries have been solved by matching the DNA of a victim to relatives or even to the murderer. It has often been suggested that a simple test of the body that may or may not be buried at Leith, or the remains that were supposedly returned to the Canoe Lake burial site after examination in Toronto, would quickly determine where, in fact, Tom Thomson lies. The Thomson family, however, has always proved reluctant. As the painter’s great-grandniece Tracy Thomson told the Toronto Star in a 1996 article about the push for DNA analysis, “Once people know the truth, that’s the end of the intrigue and the chatter about it.”

The chatter, of course, was there from the very first day, though then kept quiet and local. It was not until 1935, 18 years after Thomson’s death, that Blodwen Davies raised questions about the painter’s fate in A Study of Tom Thomson: The Story of a Man Who Looked for Beauty and for Truth in the Wilderness. In 1970, the story gained significant legs when Judge Little, one of those who had dug up the remains in 1956, published The Tom Thomson Mystery, which became an instant bestseller. A year earlier, Little had assisted the CBC in producing a docudrama that laid out the various theories on what may or may not have happened. Little had relied strongly on the diaries of Mark Robinson, the area ranger at the time, a friend of Thomson’s and a storyteller known to “embellish” freely. Robinson’s daughter Ottelyn Addison published, in 1969, Tom Thomson: The Algonquin Years, a slim volume, which she co-authored with Elizabeth Harwood.

Thomson poses in his dove-grey painted canoe, circa 1912. Photo by Edward P. Taylor Library & Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario gift of Marjorie Lismer Bridges, 1976 © AGO

Thomson poses in his dove-grey painted canoe, circa 1912. Photo by Edward P. Taylor Library & Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario gift of Marjorie Lismer Bridges, 1976 © AGO

The mystery was given new “life” by the arrival of social media. Ottawa civil servant Tim Bouma began posting on Twitter (now X) in fall 2011, imagining Thomson’s inner thoughts in less than 140 characters. “Getting quite a bit done,” was the first entry of @TTLastSpring, “but unsure what I will submit to the OSA spring exhibition.”

It was a simple idea, Bouma says.“I imagined what fun it would be to pretend that Tom had a smartphone and was tweeting in real time from the past.” In the more than a dozen years since, Bouma has posted tens of thousands of Thomson thoughts and art pieces, attracting a national and international audience. Quirky and insightful, he soon gained a loyal following for those wondering about the painter’s final 100 days of life. “I decided to leave out Tom’s fate completely,” he says, “leaving the reader to decide and the mystery to continue.” Thomson, he believes, is Canada’s “lost son—he defined the most iconic images of Canada.”

Bouma, like so very many who have become fascinated with what Winston Churchill once described another puzzle as being “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma,” believes we will never know exactly what happened.

“I believe we are beyond solving the mystery,” he says. “It is now a Canadian myth. Any definitive solution to the mystery (including mine) would take away the power of the myth.

“Better left unsolved, and let the myth and the mystery endure.”

Long-time CL contributor Roy MacGregor is the author of some 70 books, his most recent a memoir, Paper Trails: A Life in Stories. He is both an Officer of the Order of Canada and a media inductee into the Hockey Hall of Fame. He spent every summer of his childhood in Algonquin Provincial Park.